By Andrew Arnold, Jack Hunter, Teddy Jacobsen and Billy Queally

The city of Lexington has only three days of drinking water reserves to rely on if the Maury River, its sole source of fresh water, were contaminated in a catastrophic accident of some kind.

Rockbridge County doesn’t rely only on the Maury River for water and could tap multiple wells and water tanks in an emergency to provide residents with what a government official described as “several days” of water.

Buena Vista does not depend on the Maury River. It taps into groundwater for its fresh water. But it had to shut down its main well in 2010 because it had been contaminated with bacteria. The crisis forced BV to build a new water microfiltration plant that went online in 2014. A city official says Buena Vista has access to 8 million gallons of water if needed.

Freshwater eventually becomes wastewater, and all three jurisdictions complete the cycle by treating it and putting it into the Maury.

Water and sewage pipes in Lexington, Buena Vista and Rockbridge County are old and in various stages of deterioration. In Lexington, water and sewage pipes date back to the early 1900s. BV’s pipes have been in use since the early to mid-1900s. In Rockbridge County, people relied on wells—and many still do. The county began providing water and sewage services in 1966.

Because of the aging infrastructure, all three jurisdictions must maintain a defensive and expensive posture, plugging leaks and replacing water and sewage pipes one at a time because it would cost hundreds of millions of dollars to replace them all at once, according to government officials.

“There was a general phrase of kicking the can down the road, and that meant generally to put off expenses as long as you could and not spend the money to fix things,” Lexington City Council Member Charles Aligood said. “You can do that for a while, but over time it’s going to catch up to you, and what we’re seeing is that it has caught up.”

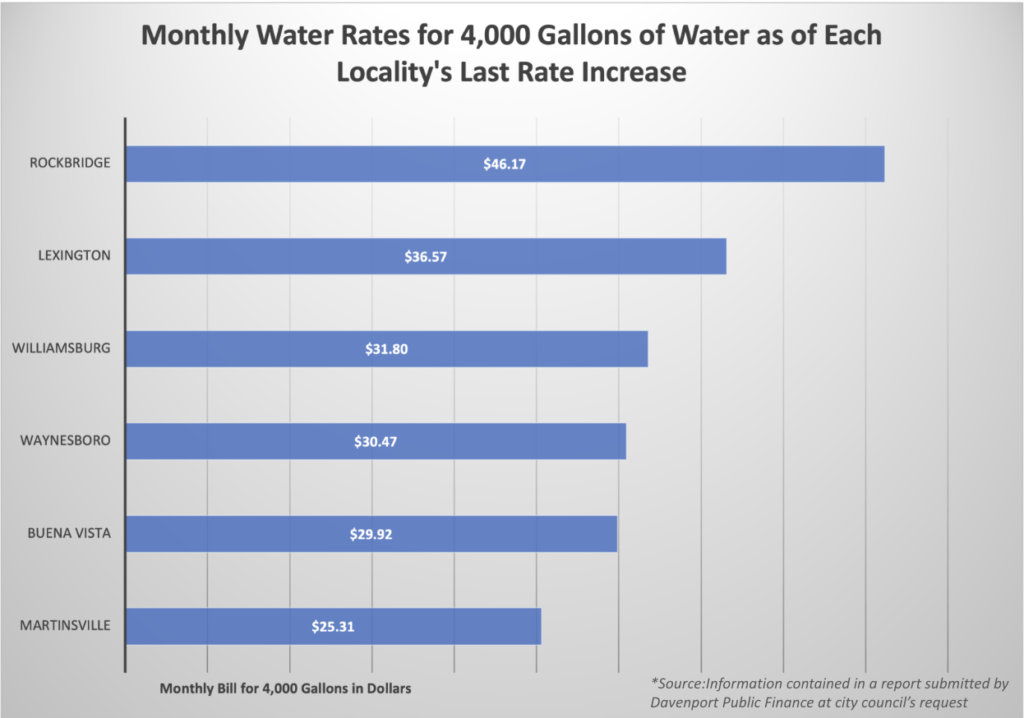

The band-aid approach means that water and sewage bills that are already higher than in other jurisdictions will likely continue to increase. As of March 2024, Lexington and Rockbridge County residents paid $5 to $15 on average for 4,000 gallons of water per month than people who live in Waynesboro and Williamsburg, according to a Lexington government report produced by Davenport Public Finance at city council’s request.

An average family of four uses about 12,000 gallons of water a month, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. That means Lexington and Rockbridge families are paying $15 to $45 more a month on average, or $180 to $540 more a year.

“Anytime anything increases, the common folk really hurt,” said David Wells, a Lexington resident and single father of three. “I mean, grocery prices are up. Gas prices are up. So, every little thing is just another notch. That kind of wears you out a little bit.”

Bill and Jess Harden own two restaurants in Lexington, and they say their water bills are already high.

“If I am spending this much more on water, it’s one less person that I can give a position to.”

Bill Harden

“The price for our water bill this month was more than our electricity and gas combined. We are using our AC 24/7 in a hot kitchen, and it still does not even come close to our water bill,” Jess Harden said.

Bill Harden said high water bills put stress on businesses, especially restaurants.

“If I am spending this much more on water, it’s one less person that I can give a position to,” he said.

Water and sewage costs in Rockbridge and Lexington continue to rise because of the constant need to repair and upgrade existing infrastructure. Lexington budgeted nearly $6 million in fiscal year 2022 to upgrade the Diamond Hill area sewer system. City council also allocated nearly $488,000 for similar upgrades in the Jackson Avenue area.

Buena Vista needs to upgrade its 38-year-old wastewater plant, which will take time. For now, the city is raising sewage rates this summer by 50 cents per 1,000 gallons so it can meet conditions that the U.S. Department of Agriculture requires for a low-interest loan to help pay for the wastewater plant’s upgrades.